Ask Better Tattooing: How Deep Does A Tattoo Go Into The Skin?

|

Listen to this Article::

|

The answer is Around 2mm, or until you get it into the dermis!

Table of Contents

Why Do We Tattoo The Dermis?

The reason why we tattoo the dermis is that it is the living tissue that has blood flow! The epidermis is comprised of a few living cells, but the purpose of it is to keep things out (that includes foreign particles like tattoo ink that don’t make it all the way into the dermis during a procedure).

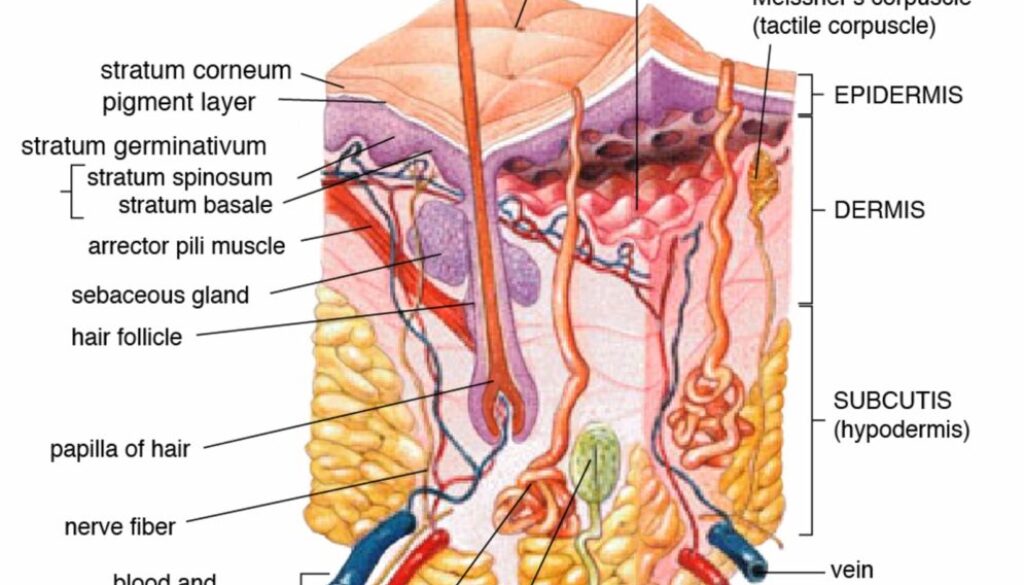

The epidermis is always being replenished, and its structure is far different than the underlying dermis. While we won’t get too involved in the actual layers of the epidermis and dermis, we do want to point out a few misconceptions that people have when talking about “skin.”

Human skin ranges in thickness is ~2mm in thickness (~.07 inches), with the thinnest skin normally being found around the eyes, joints, or other mobile aspects of the body. You can tell how thick that is by checking the thickness of a tongue depressor, which is around 2.8mm.

Yes, your skin is really, really thin!

Skin Models and Where You Put Tattoo Ink.

The model you see above is an approximation of what the skin’s structure is like (IN ALL IT’S GLORY!). Can you see those bits of yellowish-blob-like stuff at the bottom? That is the hypodermis – also called the subcutaneous tissues. For those of you without the basic knowledge of Latin – “Hypo” stands for “under,” “below,” or “slow.” Hypodermis connects your skin to your body and has a lot to do with how the tattoo is applied, how it heals, and how well the tattoo lasts… But we aren’t going to go in-depth about this either!

The main reason why the dermis is so important to the permanency of tattoos is 2 fold:

- The body’s immune system must hold the tattoo permanently during and after the skin is remodeled from a tattoo wound.

- The body’s first line of defense is a LEUKOCYTE! Many other cells deal with the wound that is created, but the most commonly studied killer cells inside tattooing are macrophages. These really rad cells gobble up (engulf or consume via phagocytosis) pigment particles, dead cells, and other foreign matter that is injected during a tattoo procedure (more on this in a second).

- There is blood flow to this part of the skin, so that means there are pathways for different hormones, signaling chemicals, and cells required to heal a wound.

- The epidermis doesn’t have vascularization, so that makes it unlikely for some of the stuff that heals a wound in the dermis to make it up to the top layers and keep it a part of the body (skipping the fact that the melanized layer has viable infection-fighting properties which are wwaaaayyyy to complex to cover here). This part of the skin is always shedding, so when you only tattoo the top layer of skin (or just don’t get deep enough to make it into the dermis), the tattoo fades from 1 week to 2 months.

Because of these two reasons, the pigment is only really viable when put into the upper layers of the dermis.

I hope you just asked yourself, “why only the upper layers of the dermis”?

Why The Upper Part of the Dermis?

Well, the deeper you go with the tattoo, the more skin you must look through to get to the image. The skin works like a semi-transparent barrier and occludes light energy coming into contact with the tattoo pigment the further into the skin it’s implanted. Imagine the skin is more like a glass brick rather than some spongy material. That brick also has a bunch of stuff all stuck through it – like blood vessels, follicles, and other things you find in the skin – which also misdirect or absorb light. The further into the “glass brick” you go, the more likely that light will bump into something and get moved around, making the tattoo look less vibrant.

At the same time, all pigment put into the skin doesn’t sit in a flat plane – like you see when drawing on a piece of paper or painting a canvas. Instead, the pigment is scattered about, coalescing into the assumption that those small particles are all aggregated together.

Take a look at this cross-section of tattooed skin. The black flecks you see are bits of black ink. As you can see, the aggregation of pigment isn’t uniform, and if you turn the image 90 degrees and imagine this image as an elevation, the pigment is stacked on top of itself.

What is Saturation?

When people talk about “saturation,” what they actually are talking about is concentrations of pigment within a given space. When looking at the cross-section again, we can assume that this space within the skin isn’t fully saturated until does have some dense pockets of pigment in specific places. Here is another photo of a lichenoid reaction associated with the implantation of tattoo pigment:

When the body has pigment inserted into it, the most viable spot for it to sit is in the uppermost layers of the dermis. The upper part is thinner and allows for greater concentrations of pigment when compared to the lower layer, which is really dense and has a lot of vessels, glands, and follicles – pigment would need to fight for this space. Your body isn’t really going to let that happen… it needs that space to reach the previously (hopefully) homeostatic space.

I also imagine that pigment implanted into the bottom layer (as well as the hypodermis) is more likely to be “pulled” into the body and end up in the lump nodes because that is where all the blood vessels are rooted… This would mean the pathway for transport by phagocytes would have a decreased distance to be picked up and taken into the body. The inflammation above these areas would result in the pigment being pushed down, further picking up extra ink as the body attempts to fix the wound created during a tattoo. (That is all hypothetical… I don’t think anyone has done a study on it, but if they do in the future, you heard it here, first!).

So, I guess the question turned out to be a little bit of a trick… which I didn’t mean to happen, but I guess I even duped myself! Realistically, the upper part of the dermis is where everything should be, but… it’s totally cool that I wasn’t thinking that hard when I wrote the question down, LOL!

A couple of other things to note –

Not everyone’s skin is the same. People with higher concentrations of melanin (darker skin tones) tend to have a higher turnover rate of their skin (epithelialization) and increased Transepidermal Water Loss factors (TEWL), thicker junctions between layers, and a greater immunological prescience attached to some processes. This means that a darker-skinned person will accept and heal a tattoo far differently than a person with lighter-toned skin.

The last thing – age thins the skin and decreases its normal ability to protect the body. As our immune system is key to the longevity of a tattoo, having it operate effectively will increase the chances of a tattoo looking good for a long time. Care needs to be taken in middle-aged to advanced-age people to ensure a level of skin health is achieved before any tattoo is done. Giving aftercare a month before the appointment, scheduling tattoos for a specific time of year over another, or taking time to break the tattoo into multiple sessions can increase the chances of a tattoo healing well and looking good for longer.

Last Thoughts:

This all means that the skin is far more complex and that each picture of skin that we identify in science is random. There is no one way to identify how to tattoo a person; rather, the entire process has to be holistic, focus on targeting the upper layer of the dermis based on age, gender, and race; and take into account each person as an individual before committing anything to the skin.

A Couple Extra Reading Spots for More Information or Just Cool Stuff:

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/body/22357-dermis

https://www.microscopyu.com/gallery-images/tattoo-at-20x-magnification-1

https://dpcj.org/index.php/dpc/article/view/dermatol-pract-concept-articleid-dp0904a03

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19469898/